“While education unlocks the door to development, increasingly it is information technologies that can unlock the door to education”- Kofi Anaan, 2003

It’s widely accepted that technology has improved education in many ways: more efficient communication, better story telling, more accurate assessment, comprehensive access to information and research, just to name a few. Unfortunately, technology has also widened the education gap between affluent and impoverished schools. Education technology (EdTech) tools are often expensive, energy thirsty, and (more recently) require high-speed internet connectivity. It is time for a new round of innovation in education-related technology that can level the playing field and bring high-quality education to where the gap is at its widest.

The Young and Disconnected

The EdTech gap is a critical but complicated issue. Providing connected devices (One Laptop per Child, Worldreader) is an important part, but not a complete solution for areas that lack the infrastructure to support those devices.

United Nations’ data estimates that only 25-30% of schools in Africa have access to electricity. More specifically, One, an advocacy group for poverty alleviation, estimates that “90 million children in Sub-Saharan Africa go to primary schools that lack electricity.”[1] This prohibits teachers from using any interactive equipment. No computers for learning typing skills (much less programing skills that lead to well paying jobs), no projectors or TVs to engage students with visual aids, and no air-conditioning or even fans to beckon them from the stifling heat in the fields, streets, and homes.

While it’s instinctive that those missing pieces would be prohibitive to education, the World Bank points out that “there is growing evidence that electricity use in rural homes is related to an improvement in education levels.”[2] Looking at the World Bank’s country-level data on access to electricity compared with primary school completion rates, there is a clear linear correlation between the two. Countries with higher levels of electricity access tend to have higher levels of primary school completion (see changes over time and interact here).

There’s no lack of empirical evidence that electricity access is correlated to higher education outcomes. A study from Tohuku University found that a 1 percentage point increase in the electrification rate in developing countries leads to an increase of 0.166 in literacy.[3] Similarly, a study conducted in India found “an increase in the electrification rate of village homes by ten percent increases predicted literacy rates in the village by 3.3 percent.”[4] Again, in another corner of the world, a study in Nicaragua found that almost three-quarters (72%) of children living in a household with electricity attended school, compared to only 50 of those living without electricity.[5]

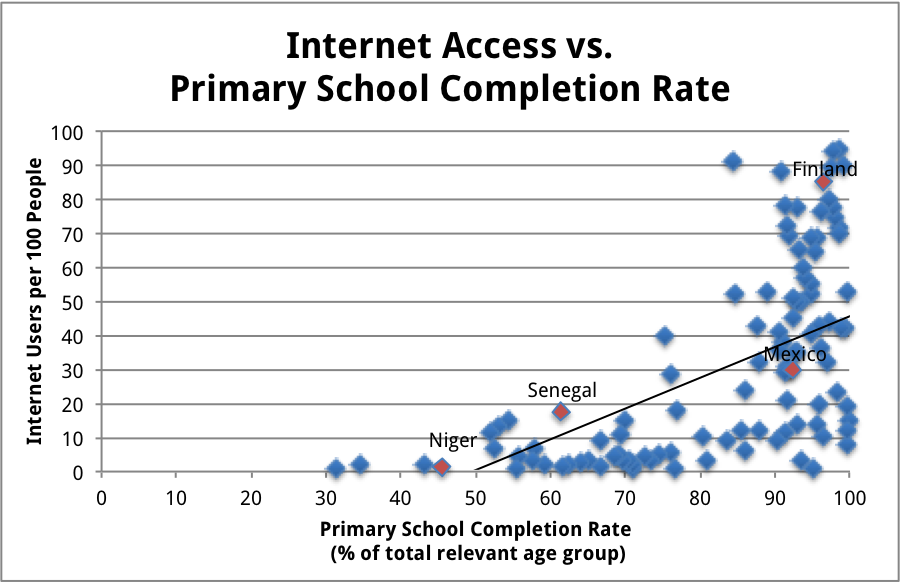

Causality is more difficult to assign, but one clear association is access to the internet. Like electricity, those countries with higher levels of internet subscribers are more likely to have better educational outcomes, as measured by primary school completion rates. You can see how this has changed over time here.

The Growing Gap

Many of the points on lower left hand side of the two charts (those with very low access to energy or low broadband penetration rates along with low primary school completion rates [PCRs]) represent countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Due to the lack of connectivity, today more than 25% of youth remain illiterate in Sub-Saharan Africa while global youth literacy rates have improved from 83.3% (1985-2004) to 89.6% (2005-2010). The subcontinent is in danger of being left behind as educational improvements favor nations that have the infrastructural capacity to accept EdTech innovations.

Sub-Saharan Africa isn’t the only disconnected part of the world, but it’s critical because it has the youngest population in the world combined with the lowest levels of primary school completion rates. The problem is going to get bigger: United Nations projections suggest that there could be as many as 2.7 billion Africans by 2050[6], with 1.7 billion youth under the age of 24. It is likely that most of the world’s youth will be living in Africa and without significant innovation they will lack sufficient education to pull themselves (and their countries) out of poverty. Sub-Saharan Africa must improve school connectivity (both electricity and communications) to maintain strong economic growth and capitalize on its growing youth population.

The Importance of Learning

Because educational attainment in Sub-Saharan Africa is far below the global standard, improving those outcomes will be paramount to continued economic development in the region. Education is recognized as the biggest driver of inequality, with a large body of literature and empirical evidence to support the notion. One study on the determinants of poverty found: “While inequalities between regions and between occupational groups and demographic groups are important, recent work (Ssewanyana et al, 2004) has tended to show that most inequality is explained by differentials within regions and within groups… education explains 25 percent.”[7]

Sub-Saharan Africa supported 6 of the top 10 fastest growing economies in the world in the last decade.[8] That’s a good thing, but there is a long way to go. The economic growth will put increasing pressure on the education system as farm employment declines and urban populations grow. As the African population shifts away from jobs in agriculture and towards urban jobs, there will need to be a more educated workforce to compete globally for jobs. Africa’s workforce will be the largest in the world: McKinsey projects it to exceed 1.1 billion.[9] “If African can provide its young people with the education and skills they need, this large workforce could become a significant source of rising global consumption and production. Education is a major challenge, so educating Africa’s young has to be one of the highest priorities for public policy across the continent.”[10] The “if” is important and will require connected schools.

It’s not just about enrolling in schools and doing well on tests, either; it’s about the long-term results of an educated population. Education is the key to poverty reduction because it is the foundation for a skilled labor force, higher household earnings, and a network effect of learning. Even in the US, there is a “digital skills gap –employees not knowing the right technology tool to use for the job or how to properly use technology tools at their disposal.”[11] This gap “is costing the U.S. economy roughly $1 trillion a year in lost productivity.”[12] In Sub-Saharan Africa, this gap is exponentially bigger as children are much less likely to be exposed to technology in the classroom.

Research shows that “[e]ducation is an important driver of household income growth and associated poverty reduction. It is crucial that education programs address issues of equity and access by the majority. The outstanding issues that inhibit access to education need to be comprehensively addressed.”[13] Comprehensively addressing the issue means leveling the EdTech gap and bringing the power of connectivity to schools across Sub-Saharan Africa.

In the coming weeks we will highlight how some of your portfolio companies are helping bridge the gap. Check back and be sure to follow us on Twitter.

[1] http://www.one.org/us/2013/07/03/a-classrooms-worst-nightmare-energy-poverty/

[2] http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTRENENERGYTK/Resources/5138246-1237906527727/5950705-1239304688925/productiveusesofenergyforrd.pdf

[3] http://www.usaee.org/USAEE2006/papers/toshihikonakata.pdf

[4] NCAER “An increase in the electrification rate of village homes by ten percent increases predicted literacy rates in the village by 3.3 percent” December, 2012

[5] http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/energy-for-all.pdf

[6] http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21598646-hopes-africas-dramatic-population-bulge-may-create-prosperity-seem-have

[7] IIIS Discussion Paper No. 203, 2007 “Determinants of Poverty Vulnerability in Uganda”

[8] http://www.economist.com/node/17853324

[9] http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/economic_studies/whats_driving_africas_growth

[10] http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/economic_studies/whats_driving_africas_growth

[11] http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/235366

[12] http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/235366

[13] IIIS Discussion Paper No. 203, 2007 “Determinants of Poverty Vulnerability in Uganda”